On any day of the week at the Potters’ Square, just south of Durbar Square in Bhaktapur, a wonderful sight can be viewed. Thousands of pots are neatly lined up all across the square and in the shelters around the sides of the square with the potters busy at the wheel as they turn out more and more. Terracotta pots and containers of all sizes and shapes crafted by potters, locally known as kumhars/kumhale or kumbhakars, are on display. High round pots to hold grain, medium-sized one for water, other products serving as containers for tea, dishes for yogurt, holders for the coal of the smoking hookah pipes and oil lamps abound.

The square itself has two small temples, a solid-brick Vishnu temple and the double roofed Jeth Ganesh Temple. The latter is an indicator of how long the activity all around the square has been going on as it is believed that the temple was donated by a wealthy potter in 1646 – to this day its priest is a potter. Pottery is very clearly what this square is all about. Under the shady open verandahs or tin-roofed sheds all around the square, the potters’ wheels spin and clay is thrown. In the square itself, literally thousands of finished pots sit out in the sun to dry, and are sold in the stalls around the square and between the square and Taumadhi Tole.

HISTORY & TRADITIONS

The pottery craft of Nepal is of ancient origin. Archaeological excavations in the Kathmandu Valley and in Lumbini, the birthplace of Lord Buddha, have revealed shards of ancient pottery in red, brown, and black shades in remarkable designs These, it is conjectured, can be dated to the Buddhist chaityas of the first and second century BC. Terracotta temples, displaying superbly carved life-like motifs – built between the 14th and 18th centuries – have stood intact in Nepal for thousands of years. The motifs and polish used are almost unaffected by centuries of denudation.

PRACTITIONERS

The making of pottery is not only confined to the hereditary caste of the kumhale but is also practised by farmers at lean agricultural times as an additional source of income. There is a brisk sale of pottery in Nepal during the winter season. The pots are reasonably priced and if no ready cash is available they are be bartered for food-grain. The potters themselves carry their pots in baskets strung on to pole across the shoulder and reach almost every house in winter to sell their produce. These potters – from Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Thimi can be seen on the streets usually before festivals.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

Pottery clay is found in both the Kathmandu Valley and in the Pokhara Valley. Depending on its plasticity a selection of clay is made by the potter. After mining, the big lumps are crushed and the dry clay is stored as it needs to be kept away from the sun for a week so that is does not lose its moisture and pliability. Like manufacturers everywhere the potters are most worried about the supply of raw material. In the old days, the dyo-cha/ black clay could be had for the asking. Most of the clay used to come from the village of Sipadol towards the south of Bhaktapur. The potters exchanged earthenware with the farmers for clay from their fields. Now, with the building frenzy, and as more and more rice fields are buried under concrete, the potters haplessly watch their supply of clay disappear.

The Nepalese technique involves mixing black clay with local gicha clay in equal proportions and adding one-tenth of its weight in sand. The whole mixture is kneaded by foot to a dough-like consistency. The kneaded clay is kept in a damp and dark place till it is required. For the wedging a lump of clay is rolled until the potter is satisfied with its plasticity.

Various styles and types of pottery products are crafted in Nepal using techniques – such as hand-forming, coiling, moulding, and the throwing – that suit the requirement of the product that is to be crafted.

In Nepal, the hand-forming technique is used to make, among other things, small terracotta products like the oil-fed lamps or palas, used in Hindu temples and homes all over Nepal – these palas are lit to celebrate the festival of lights, Dipawali.

The coil pottery technique is used in Nepal to make large storage pots and basins for washing (attals). These large pots are crafted by shaping the clay first by hand and then by beating them into shape with a wooden mallet. In this technique the potter starts at the bottom and then builds upwards, layer by layer, by adding lumps of clay to the edges, painstakingly raising and shaping the wall of the jar, after each addition of clay, until the required height is obtained. Between each addition of clay the potter waits for the mass to harden before raising the wall further. When the required height is reached, the vessel is left outside to dry in the sun. In order to ensure that the walls of the jar are of uniform thickness the potter beats the inside and the outside surface with a wooden mallet. A smooth finish is obtained by rubbing the surface, while the rims and edges are smoothened with water.

This coiling technique is sometimes coupled with the throwing technique on the potter’s wheel. This is usually done while making water storage pitchers. In making such pitchers, the potter uses the wheel to build the shape of the thick walled vessel and follows it up by hammering the clay inside and outside to get the final shape and size. The beating is done at the same point from both the inside and the outside. Very fine sand is used to coat the mallet to avoid it from sticking to the clay surface while beating. This process is known as batting.

Wooden, terracotta, and Plaster of Paris moulds are used for making those products that cannot be shaped on the potter’s wheel. Smoking pipes (chilims) and hexagonal fire-pots (makal) are made using this technique. A lump of clay is uniformly hand pressed against the inner walls of the mould into which fine sand has been sprinkled. The form, when baked, comes off the mould when it is turned upside down. A wide range of products with complicated shapes and designs are produced by this method; by joining different parts and kneading the joint edges together by hand, complex terracotta products are built up.

The throwing technique has its roots in antiquity. The potters use a large wheel of hard wood, which is similar in design to the Indian wheel that is supported on a wooden pivot and rotated with a long wooden pole. The wooden wheel is now being rapidly replaced with the ingenuous use of a discarded truck tire! The potter places a lump of clay at the centre of the wheel, the wheel is rotated swiftly, and the potter uses both hands to shape the pots, using the outward and upward motion. The finished pot is sliced off the wheel with a cotton thread or wire and kept aside for drying in the shade, though the final drying is in the sun. Often the pots are polished by rubbing their outer surface with a smooth fruit seed (lekh pangra), while the bottom of the pot is beaten to give it its final finish. At all times the potter has to ensure that the pots do not crack The height and diameter of the vessels are measured using traditional bamboo or straw, while the application of the clay-mud slip is made with a cloth swab. The dry pots are then stored for firing.

The famed black terracotta of Nepal is also made on the potter’s wheel. However to achieve this unusual look the potter adds a few more steps to the process of production. When the pot is sliced off the wheel and dried and hardened completely, it is placed on the wheel again and the outer surface is rubbed with lekh pangra or with a horn till the surface acquires a glossy shiny finish. It is then fired in an open kiln. When the firing is about to be completed all the openings are closed and the pots are baked in the enclosure with an insufficient supply of oxygen. This produces a great deal of smoke inside the kiln and carbon particles get deposited on the outer surface of the pots, imparting a shiny black surface to the vessels. The potters of Bhaktapur and Thimi are famed for their skill in producing the black pottery. Traditional black pottery items include soma, dhelancha, and thyakacha.

Firing of the pottery is usually done before the advent of winter. The pottery is fired at a temperature of about 600-8000 C. This low temperature firing of the pots produces weak earthenware. At this temperature the pots are basically baked and they acquire a reddish tone and produce a sound when tapped. Great care needs to be taken in their arrangement and movement as they are only bisque-fired.

The pots are fired in the open, either in courtyards or in the fields. The potters use rice and wheat straw, with a thick layer of about one foot of it spread on the ground. Large sized pots – often the water pots – are placed over this layer in a circular fashion. Another layer of straw and dry grass, about six inches thick, is spread over them. Next, a layer of slightly smaller pots like the washing vessel (attals) is placed over this. In this manner several alternative layers of dry straw and pots are stacked carefully. Small items are placed at the top and covered again with straw and dry grass. Thus these pots are arranged in rows with the big ones forming the bottom layers and the smaller ones on top in alternating layers to a height, 4-5 feet. The whole stack is covered with a one-foot thick layer of straw and dry grass. Finally the entire stack is covered with about a four-inch thick layer of ash. The layer of ash applied outside has a two-fold function: it to prevents the air draft; and maintains the heat inside the kiln for a longer period. The finished kiln resembles a small mound and at its base two or three holes are made with long sticks. The fire is lit at the bottom and the firing continues usually for about 24 hours. The potter controls the rate of flow of oxygen and allows the straw to burn slowly. If there is an excessive supply of oxygen the straw burns too rapidly, leaving the pots unbaked. As the fire rises slowly upwards the pots are baked. The potter keeps a constant watch on the kiln and manipulates the heat by making two or three holes in the upper part of the kiln to help the baking by introducing more air drafts. A dark red heat is seen inside the kiln and the temperature reaches around 600-7000C. When the whole stack burns completely and no more smoke comes from the kiln, it is allowed to cool for two days. The pots are taken out individually and the ash deposited on them is removed. The pots are now ready for sale.

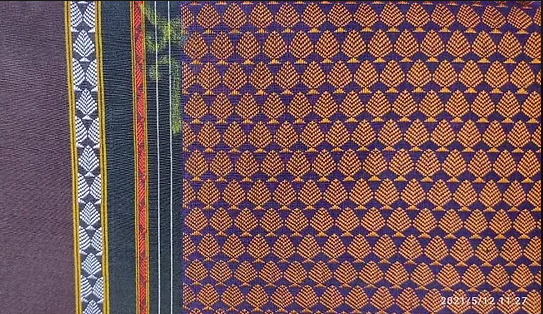

PRODUCTS

The product range includes high round pots to hold grain, massive liquor vats, medium-sized ones for water, products serving as containers for tea, dishes for yogurt, holders for the coal of the smoking hookah pipes and oil lamps. In addition to the traditional household utensils there are candle-sticks, ashtrays, sacred images and masks, and elaborate flower pots. One of the most popular items is a flower pot shaped like an elephant, with a hollow in the elephant’s head to plant flowers.

In present times pottery is largely crafted for utilitarian purposes. These large container jars, water pitchers, lamps, washing bowls, flowerpots, vases, smoking chilims and objects used in religious ceremonies are some of the products being produced. Farmers store their agricultural produce in large earthenware jars for protection from rodents and damp. The jars are also used for water storage and for carrying water from the well and water spout. One of the most important pottery categories is the making of lamps. Clarified butter (ghee) fed lamps are burnt on special festive occasion such as Dipawali, the festival of lights. Lamps are lit while worshipping in temples and for various Hindu and Buddhist rituals, and the use of lamps in homes is also an old tradition. Besides earthenware, other clay products such as bricks, roof tiles etc. are produced in great quantity all over Nepal.

Gallery

YOUR VIEWS

PRACTITIONERS: INDIA

Access 70,000+ practitioners in 2500+ crafts across India.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

10,000+ listings on arts, crafts, design, heritage, culture etc.

GLOSSARY

Rich and often unfamiliar vocabulary of crafts and textiles.

SHOP at India InCH

Needs to be written.