Wooden architecture and wood-carving are inextricably linked in the traditional wooden architecture of Sri Lanka, especially in Kandy, the central province of the country. The allied skills simultaneously highlight the construction and carving skills of master-craftsmen and architects; Kandyan wooden architecture is extremely rich in detailing, show-casing a range of wood-carving, much of which represents a remarkable combination of creativity and skill in manipulating the material.

The abundance of several varieties of timber was instrumental in the prolific presence of wooden architecture. Owing to its durability and hardness, timber was used to make several structural components like beams and massive pillars, as also elaborately designed doors and windows. The traditional craft of wood-carving was practised by several highly esteemed crfatsmen and master-craftsmen, who trained apprentices in the principles of the craft.

Mastering the skill of wood-carving often precedes initiation into carving on ivory, an extremely delicate and esteemed craft. There is a strong link between the two crafts: once an artisan carving on wood has graduated to ivory-carving he is believed to have reached the pinnacle of his craft. The descendants of master ivory carvers of yore carve in wood when ivory is not available.

TRADITIONAL WOODEN ARCHITECTURE AND WOOD-CARVING

Some examples of mediaeval masterpieces in wooden architecture that have survived almost intact are the roofs and pillars of the Embekke Devalaya, the Audience Hall of Kandy, and the ambalamas or resting places of Panavitiya in Colombo district and Mangalagama in Kurunegala district. Examples of elaborately detailed wooden architecture of the eighteenth century are located mainly in and around Kandy in the devales (temples), viharas (mansions) and palaces, and pansalas (Buddhist places of worship). Sumptuary laws forbade elaborate domestic architecture in ancient Sri Lanka. Only the king’s palace and religious buildings were allowed to have doors with ornamental tops and lime plaster. Dwellings of ordinary citizens had thatched roofs, though those of the highest rank were permitted to have tiled roofs.

Wooden pillars or kapa found in temples, mansions, and palaces all over the country have intricately carved designs, with the lion or gaja simhayo, hamsayo, and dancers being common. The pillars were either of the same diameter throughout or tapered slightly; the shaft was octagonal with a rectangular base and capital. Cube-shaped projections were also found intermittently throughout the length of the pillar. The octagonal facets of the pillar were carved with designs of the bo leaf, and the capital of the pillar was carved with motifs of garlands of pearls or mutu dela. The base of the pillar was carved with horizontal stepped incisions or asana-kadaya. The points in the pillar where the rectangular shape changed to octagonal were softened by the design of cobra’s hood or naga bandha or else the liya pota ornament ( geta-liya-pota). Wooden pillars usually rested on a stone base.

A separate carved capital or bracket (pe-kadaya) was located where the pillar supported the beams. This was carved with decorative designs, usually pendant lotus forms from the mouth of the serapendiya; the downward face of the flower had the figure of the dancer or the design of a hamsa-pattuva or bird was found in place of the petals. The rafters of the ceiling were also elaborately carved. Usually there was a pala peti moulding at the inner angle and a liya vela or a branch ornament in the front. At the base on either side was found carved representations of either a guardian deity in low relief or the figure of a dancer or elephant. Above the figure in low relief was the inscription ‘ASANA KADAYA’ characteristic in Kandyan woodwork.

Door-jambs made of wood were treated similarly: the design of the geta liya pota or naga bandha was from where the rest of the carved jamb began and continued. The lintel of the door could be straight or arched and plain or carved. Sometimes the carving was done on ivory as embellishment for the door; in this case the door-jamb itself was not carved. The bolt post and the bolt of the doors were carved with restraint, so that the decorative aspect would not interfere with the utilitarian one.

Windows were designed as smaller versions of doors. They either had single or two-leaved doors-shutters or else were fitted with lacquered or turned wooden bars with no shutters. Traditionally wooden mosaic work was very popular in Galle and other areas in the southern part of the country.

EXAMPLES OF TRADITIONAL WOODEN PRODUCTS

1. FURNITURE & BOXES

The beds made in Sri Lanka display European influences, especially Dutch styles. These have a wooden frame of four parts with four legs or kakul; the legs are thirmed and chafered or turned and lacquered. The low head-rest or head-board is often finely carved.

The ancient hour-glass shaped cane stool is still in use, as is the low stool or kolombuva. The three-legged bankurva is more ornate. These stools are beautifully carved and usually have flat legs. In ancient times no one except the king was allowed to sit on a chair with a back; these chairs were elaborately carved and painted or inlaid with ivory, a practice that can still be found. Tables or altars for offering flowers, dagabas or bo leaves before images are generally in the form of a bench. The legs are carved or turned or flat with a double bend or rectangular shape with a double bend.

Wooden chests were used by royalty and in places of worship to store cloths, insignia, or ecclesiastical property. Indo-Portuguese styles with hinged lids and big locks were common; the boxes have decorative metal bosses over rivets. Along with European influences in boxes, caskets, and furniture some carving styles like rococo were also adapted and used by the artisans. These are more often found in the north of the country like Jaffna where the Western influence is strong; in the low-country or in the south a type of bible-box, showing Dutch influence, has been found. These were usually made of calamander or ebony with scallopings and flutings. In Matara district in the south, a work box made with trays and lids inlaid with ivory has been found. Dutch influence was also visible in the introduction of products like the Burgomaster chair.

Elaborately painted book-boxes or presses used in temples or pansalas have been found in Kandy; the lids are set with gems. In temples, elaborate boxes were used to store valuable insignia and came to be known as abharana petti or regalia box. These are sometimes adorned with lac applied on a lathe. Rare woods like ebony and calamander are used sparingly, with ebony being used in combination with ivory for inlay work. Turned jewellery boxes and boxes to store betel leaves are common. Some of the book covers in the eighteenth century were also carved out of wood.

2. KITCHEN ITEMS

Hendi-ana is the name given to spoon racks in the kitchen. These racks are suspended from a beam. The long handles of the spoons are set in the holes. Spoons and the handles of vessels have designs carved on them: dancers, musicians, and wrestlers as well as mythical animal and bird motifs. Spoons and sweetmeat moulds ( sini pittu katu) made from coconut shells (pol-katuva) with carvings are common. Water dippers or kinisi made of whole coconut shells with beautifully carved wooden handles that are passed through and pegged inside are also made. The coconut shells are elaborately carved and sometimes silver-mounted.

The coconut scraper or hiramanaya is a shaped log or kolombuva having a toothed disc as a rasp; the vap-pihiya or vegetable slicer has a bill-hook set edge upwards in a wooden holder. The user can actually work both devices simultaneously. The coconut scraper set in the form of a book-rest is known as yatura-hiramaya. Wooden flat-cake moulds and jaggery moulds are carved with representations of elephants and lions (olinda poruva). Granary seals are also made of wood as are string rice presses.

3. IMPLEMENTS

Agricultural implements like plough or nagula and scraper or poruva, as well as laha and kuruniya measures and bells or clappers for animals are made of wood and usually ornamented.

THE CONTEMPORARY PRODUCT RANGE

1. Wood Sculptures & Figures

Wooden sculptures have become a popular craft item, owing to increased demand from among the visiting tourist population. This has encouraged the carvers with the special skills of carving and sculpting to similar figures of humans and animals in flat or round shapes singly and in groups. This skill is predominant in the southern part of the country. The themes for these sculptures are not just statues of Buddha and gods but also include compositions of scenes and events drawn from local history, legend, and contemporary life.

The products are usually carved from hard woods like ebony, palu, sandalwood, gam–malu, and na, which are close-grained woods. Statues of Buddha are usually carved out of sandalwood. The tools used to make figures out of wood include simple items like hand-saw, chisels of various sizes, mallet, and a divider and square. An adze is used for shaping the log, and chisels of different sizes and shapes are used for carving.

A piece of wood is first selected and a rough shape is chiseled out on it through a process known as baragahanawa. After this, the actual features are delineated: this process, executed with fine chisels, is known as mattangahanawa. This image is then smoothened out and polished.

Among all the animals that are carved, elephants occupy pride of place; this is especially true of artisans working with ebony (Diospyros Ebenum), a prized variety of timber. Ebony elephants are primarily crafted in the Galle region, which is in the southern part of the country. Elephant figures are carved in big and small sizes and are also carved arranged in a row. Ebony wood is too valuable to be wasted and some of the other items carved out of it include ash-trays, walking-sticks, jewellery-boxes, gift-boxes, pen-holders, household items, wall hangings, fancy jewellery, figurines, sculpture, ornamental products and seasonal decorations. These items are carved from even bits and pieces of ebony. Porcupine quill inlaid on ebony and other hardwoods in delicate designs make lovely jewellery-boxes, ash-trays and stools. Ebony is obtained from the ‘Dry Zone’ of the country so the artisans who involved in ebony-wood carving have moved form the southern district of Galle to regions like Anuradhapura, Sigiriya, and Polonnaruwa, all in centres with a high tourist population. Satin and teakwood are also used.

The products made out of ebony like elephants, and sculptures of gods and human figures command very high prices in the market. Ebony elephants from Sri Lanka are rated as valuable export earners. The artisans who find ebony too expensive use hardwood and sometimes colour a cheaper variety of wood black for their use.

Some of the problems faced by this craft are that supplies of ebony supplies are dwindling in the country due to rapid deforestation; the government has also decided to exercise controls on the same. The wood supplies are. The craftsmen are unable to purchase ebony in sufficient quantities to pursue their craft. This lean period in the ebony wood craft industry poses a challenge to the artisans who have to make use of other woods for creating carvings and sculptures and animals which must appeal not only to the visual sense but also to the tactile sense.

2. Wooden Toys

Wooden toys were mainly made for the local market a decade ago when the foreign toys were too expensive and not easily available. The quality of toys made today are so good that they are exported to a large extent. Wooden toys from Sri Lanka are rated as high export earners. Some of the wooden craft items made for children are toys like puzzles, alphabet sets, book-ends, and games which are educational in nature along with accessories and nursery items. Some of the processes in the craft-making technique are mechanized; this means that those stages of the craft that are done by hand get maximum attention.

The wood types used to make the toys include mahogany, teak, ebony, and even softwoods, all of which are moulded again to meet the market requirements of colour, design, and quality. These toys are by and large hand-made and are painted with non-toxic paints. They provide children with the opportunity to develop hand and eye coordination and motor skills along with encouraging creativity and imaginative play. These toys satisfy the general international toy-regulations like health and hygiene along with the needs of educational psychology.

There are a special group of artisans who reside in Moratuwa and its environs – on the western coast of the country, close to Colombo who carve out miniature models of European cars like Rolls Royce and Benz almost to perfection. This highlights their astonishing wood-crafting skills. These toy-like miniatures are daintily constructed and finished to look like the original in every detail; they are highly in demand by foreign buyers.

Important locations include:

- Colombo district: the villages of Moratuwa, Boralesgamuwa, Angoda, Peliyagoda, Mount Lavinia, Pannipitiya, Colombo, Nugegoda, Kesbewa, Malabe, and Ratmalana.

- Galle district (in the south of the country; 148 kilometres form Colombo): the villages of Kalegana, Kumbalwella, Wekunegoda, Kapugampola, Wataraka, Peduruwa, Milidduwa, and Osanagoda.

- Gampaha district (next to Colombo): the villages of Mahara, Negombo, Pelawatta, Weboda, Ganegama, Mirigama, Attanagalla, Kadawata, Gampaha, Weliya, Kopiwatta, Udugampola, Katana, Weke, and Minuwangoda.

- Jaffna district (northern-most tip of the island): the villages of Puttur West, Irumpalai, Pathamani, Kopay North, Puttur East, Atchuveli, Ureluand, and Madduvil South.

- Kegalle district: the villages of Garagoda, Angunwela, Utuwankanda, Karandupaha, and Ambulugoda.

- Kilinochchi district (northern part of the country): Kilinochchi itself.

- Matara district (in the south): the villages of Tudawa, Watukolakanda, Thumbe, Henegama, Dondra, Wepothira, Kirinda-Magin-Ihala, Kahandugoda, Malimbada, and Kapugama.

- Mullaitivu district: the villages of Puthukkudiyiruppu, Pannanhanmen, Mulliyavalai, and Mulaitivu.

- Nuwara Eliya (next to Kandy) the village of Kotmale.

- Pollonaruwa district: villages of Sudukanda and Ataragollewa.

- Puttalam district (north-western coast): the villages of Kalaoya, Morakele, Chilaw, and Nattandiya.

- Trincomalee district: village of Kantalai, Trincomalee town, and Tiriyaya.

- Vavuniya district: in Nelkulam.

3. Quillware

The quillware craft which is combined with wood for inlay-work is found in the villages of Kumbalwella; Peduruwa in Galle district; and in the village of Kamburugamuwa in Matara district. Furniture items like teapoys and octagonal tables along with fancy boxes are made from inlay of porcupine quills on ebony wood.

4. Handcrafted Wooden Furniture

Design concepts from Europe are prevalent in the styles of furniture made on the southern and western coastal districts of Sri Lanka. As mentioned earlier, there has been a lot of Portuguese and Dutch influence in furniture styles, in the workmanship of tables, chairs, chests, almirahs or storage cupboards, work-boxes fitted with decorative hinges, locks and handles; this is very reminiscent of the Renaissance style of furniture. The Burgher community in Sri Lanka are a small minority of Dutch descent; they are found scattered all over Sri Lanka, mainly in the south and north. In their houses a lot of pieces of the kind of furniture mentioned above can be found.

In the early stages of furniture-making in Sri Lanka Kandyan furniture were greatly influenced by the prevalent architecture in terms of design and form. At a later stage the furniture made became an integration of Sinhalese decorative elements and Dutch styles of furniture-making. The churches in Sri Lanka have always exemplified the influence of Dutch architecture; this is especially seen in the wooden doors, windows, pillars, and roofs. Some of the churches which exist to this day showcase the high standards of craftsmanship in timber work and furniture. The skills that were introduced by the Dutch in Sri Lanka through their mastercraftsmen and superintendents of work (Baas in Dutch) and the influence of Indo-Portuguese and Indo-Dutch styles laid the foundation for the development of the craft of furniture-making.

Java and the Malabar region in India has also exerted influence in styles of furniture-making; these styles were integrated with the European styles with some Sinhalese design inputs to make furniture suitable for Sri Lankan conditions. Sri Lanka has always been blessed with abundant natural wood-resources in terms of high-quality timber and hardwood; in fact during its colonial regime the surplus wood was exported to satisfy the demands overseas. The type and quality of the timber has always determined the form of the final product. These woods may have been highly ideal for displaying carving skills and elegant workmanship but they were most certainly a test for both the tools and the craftsmen.

Ebony furniture has always been considered prestigious because it was used mainly by the aristocracy and the affluent classes; the kind of furniture made from it were sofas, couches, chairs, tables, and almirahs or storage cupboards which were embellished with inlay-work and carving. In the region of Galle which is on the southern coast, descendants of the mastercraftsmen of yore still practice their craft. They display their traditional skills by making teapoys in black or white ebony with porcupine quills embedded in a design or octagonal tables with ebony pieces or other woods inlaid in a decorative pattern. The skills that are involved in making such items of furniture are highly traditional and are in danger of disappearing altogether due to scarcity of raw materials and the aging of the surviving masters in this craft. Some efforts will have to be taken to ensure that these skills do not just die out. As far as the contemporary times are concerned, calamander is hardly used nowadays as it is unavailable. Tamirand wood is also hardly used for furniture today in spite of its fine grain and colour. Satinwood was used till recently especially in the Kandy region for the woodwork of religious buildings, mansions and for fashionable furniture. It has always been considered a high-quality decorative timber in demand all over the world.

Teak and nadun have been popular among artisans and carpenters due to their lightness, durability, and the emergence of an attractive grain after polishing. Mahogany and soft woods are also used to a great extent. The other types of woods that are used are halmilla, kumbuk, and suriya. Mara wood is used for heavy furniture as it is ideal for the purpose and gives the finish of a good wood. Woods like sapu and kolon are of a lower grade and have also become scarce nowadays. In the northern part of the country, kohomba wood has always been highly valued for the making of chests and linen cupboards. The whole range of tools that are required for making hand-crafted furniture are a full set of carpenter’s tools, saw, planes of different sizes, chisels of different sizes, mallet, hammer, divider, hand-drill, bevel, tool-sharpeners, pillars, files, bench-vice or screw-drivers and clamps and a work-bench. Mastercraftsmen in wood have settled down over time in the region of Moratuwa and its environs; Moratuwa is situated close to Colombo. Moratuwa, therefore has become the main centre for making furniture of high quality. Over years the artisans have developed their skills in improving the quality of their products to meet the growing demand for new styles and new forms of furniture. Timber scarcity of a high magnitude faces the country and is a major bottleneck in the growth of this craft.

Rubberwood is slowly emerging as a viable substitute for hardwood timber to make good-quality furniture. Some of the items of furniture crafted out of rubberwood are chairs, tables, and desks. Boron treated rubberwood or Borwood is now being widely accepted as a raw material for making furniture of a satisfactory standard. Markets abroad have also accepted borwood which implies good future prospects for the steady growth of this craft.

Hand crafted wooden furniture has Moratuwa as the main centre which is close to Colombo. Some of the other locations are as follows:

- Batticaloa district (on the eastern coast; about 370 kilometres form Colombo).

- Ratnapura district: this craft is found in the villages of Opanayake and Gawaragiriya.

The important role furniture plays in the décor should be kept in mind for future plans in the development of this craft. This factor is significant in deciding the designs and styles of the furniture made. Furniture is mainly designed to fulfill the purpose of giving the right tone and setting to a room to showcase the accessories in it. The future of this craft will be bright if new refreshing design concepts emerge showing new paths the craft can take keeping in mind the changing tastes and trends; this will expand the markets and give it the much needed boost and encouragement.

TOOLS USED IN WOOD CARVING

Traditional carving was done using just a small selection of chisels. The repertoire of tools has gradually evolved: the

basic ones are as follows.

- The riyan lella or cubit-rule.

- The lamba-ketaya or plumb-line.

- The nul-lanuva or line or tape.

- The kava-katuva or compass.

- The mattam poruva or set square.

- The li-palana-katuva or wedge.

- The kulu-gediya or sledge hammer.

- The porava or axe.

- The at-veya or small adze. & the loku-veya or large adze.

- The at-koluva or mallet.

- The mitiya or hammer.

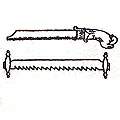

- The tahadu-kiyata or saw; the at-kiyata or hand saw; & the haraskapana-kiyata or timber saw.

- The yatu-ketaya or straight plane; & the ravum-yatu-ketaya or curved plane.

- Chisels of various sizes: loku-niyana, niyan-katuva, & kalambu-niyan-katuva.

- The gal-torapanaya or stock-drill & the at-torapanaya or hand-drill.

- The iri-gahana-katuva or scoring tool.

- The vidina-katuva or awl.

- The gijulettu-katuva or gimlet, perhaps of European origin.

- Rasps: the pullorama, peti-, vata-, loku-pullorama.

- The pira or file.

- The vadu-riyana or foot-rule measuring a carpenter’s cubit, which is divided into 24 angal or inches.

The tools are sometimes ornamented with lacquered handles or damascened with silver. Several traditional tools have been modified for use in today’s times; innovations and special tools are also made by the craftspeople as and when required. Some parts of the craft-process has become simpler with the introduction of wood-working machines; designing and carving, however, remain individual expressions of creativity.

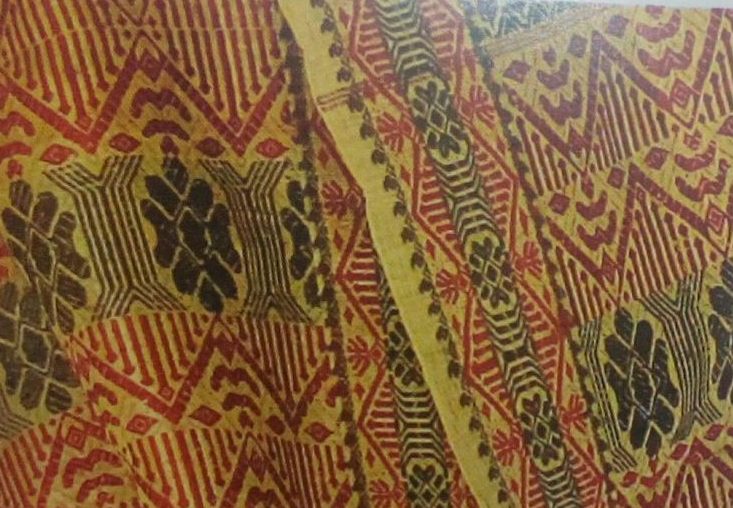

DESIGNS & MOTIFS

The designs used are mostly of traditional Sinhalese origin. Furniture, as mentioned, shows the influence of Dutch styles, with fluted and bowed legs and relief carving. Flat treatment of carved wood is found in chip carving of beds; greater relief carving is found in door-jambs, pillars, capitals, and bolts. The treatment however remains severe and the stems of the foliage are flattened rather than being rounded or undercut. A characteristic feature is that the outlines of stems and interlaced work are emphasised with an incised line next to the margin on each side. Headboards of beds are pierced and carved, thus giving an appearance of greater relief and light and shade. Incised outlines are found here on flat surfaces. Wood-carving used for decorative purposes was usually painted. Turned wood is found in the feet and legs of benches, beds, and seats; it is found more often for window-bars, balcony-railings and vehicles. Sometimes handles of bill-hooks and cressets are half-turned and half-thirmed. Turned wood is usually lacquered in red, yellow, green or black.

Some of the motifs that are widely used in wood-carving include:

1. BIRD & ANIMAL MOTIFS

-

Kindura: Derived from the popular Jataka tales, this is a half-bird and half-human motif, with the lower half shaped like a bird. In the treatise Rupavaliyait is called kinnara and described thus: ‘The Lata Kinnara hath a tuft of hair on the head, a garland round the neck, but the nether part is like that of a bird, with wings; a face fair and radiant, a neck graceful as Brahma’s.’ Intricate versions of the liyapath (leaf-like formation) motif are found on the tail of the kinnara.

- Et-kanda-lihiniya: This is a mythical bird of prey having the head of the tusker and the body of the bird; in popular legends it is known as a monstrous bird preying on elephants. The head is depicted with the natural form of a tusker and the tail has the liyapath.

- Makara: This is a traditional Sinhalese motif that, according to the treatise Rupavaliya has the trunk of an elephant, the feet of a lion, the ears of a pig, and the body of a fish, with its teeth turned outwards, eyes like the monkey-god Hanuman, and a tail. This is found widely at the entrance to Buddhist places of worship, erected above temple doorways, and also above images as the makara torana. This motif was very popular in the eighteenth century; perhaps the most spectacular aspect of it is the tail.

- Simha: The lion is said to be the mythical ancestor of the Sinhalese and is considered a symbol of majesty and power. The mythical forms of the lion motif are the kesara sinha (the face of the lion) the gaja simha, (figure of a lion with an elephant’s head) and nara simha (figure of a lion with a man’s head). This motif is widely used by the wood-carvers, some of whom have evolved further variations of the motif. The kimbihi muna is a mythical lion face found in wood-carvings on the doorways of temples, along with makara torana; an example is found in the Embekke temple and on the lintels of doorways of other mediaeval temples.

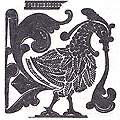

- Hansa & hansa puttuwa: These are mythical-divine birds widely found in Hindu mythology. They are respectively a mythical bird (eagle with two heads) and a divine bird. These motifs are all widely used in wood-carving today to embellish the various wooden craft products.

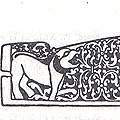

- Vrishaba kunjaraya: This combination of elephant and a bull is found in carved wooden pillars at Embekke; other motifs found on this pillar are bherunda pakshya, hansa, and hansa puttuwa, which are bird figures.

2. HUMAN FIGURES

Figures, natural, divine, supernatural, and mythical, either static or in action (dancing, wrestling, combat, acrobatic feats, among others) are found widely in wood-carvings, especially in carved friezes. The carvings in Embekke, Panavitiya, and the Dalida Maligawa or the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Kandy have an abundance of such figures. In an interesting innovation, human figures are arranged to create inanimate motifs – four wrestlers form a chariot wheel, while two represent a dagaba or vase, and a palanquin. The narikunjara motif, a combination of several female figures to form one design, is quite common in wood-carvings. The Panch-nari-ghataya, combining five youthful female forms to create a pot, is one variation.

3. FLORAL MOTIFS

-

Liyawela: This is a combination of leaves, branches, flowers, buds, and tendrils trailing from a sinuous creeper and forming a symmetrical pattern. When two creepers are intertwined with unvarying uniformity, the design is known as dangara vel and when the creepers are linked with another motif the design is known as vel puttuwa. This is used either as a border design or to fill in the empty space in an already existing design. This design begins from the mouth or tail of a mythical or natural bird; sometimes even from flowers like lotus.

- Liyapath/liyapota/liyapata/liyapotha: This is a leaf-like formation composed of the double curve or vaka deka, the basis for various elaborate decorative motifs in Sinhalese art. A motif that involves several liyapath formations grouped together in a symmetrical pattern is known as the liyapath vela. This is found frequently on round-shaped wooden objects. It is also used to adorn the tails and crests of bird designs, tails of mythical figures (kindura), the manes of lions, and the handles of door-bolts and water-dippers.

- Annasi mala: The pineapple flower is used in its decorative version in wood-work, especially as the katuru mala or katiri mala: it has crossed petals resembling a pair of scissors and has the vaka deka or double curve as its basis.

- Nelum mala: The lotus flower is perhaps the most frequently used motif in Sinhalese art. The design is usually found within a circle; however in the wood-carvings at Embekke, it is found within a square. The pala peti is a motif derived from lotus, found mainly as a border design. The variations range from a simple petal with additional features like darts, crosses, semi-circles, and snake-hoods. Very common in mediaeval times, the motif continues to be used in present times.

- Sina mala: This is a ‘conventional’ flower form, widely found in wood-carvings. It is often conjoined with the vaka-deka, depicted as a flower-spray from the mouth of the beast, or attached to the stem of a liya vela.

- Bo pata (Ficus Religiosa): The leaf of the bo tree, considered sacred for Buddhists, is used prolifically as a design element. Variations of this motif are frequently seen in wood-craft.

-

Knop & flower: This is a leaf and flower combination, alternating to form designs that are mostly used as a border or edge of an article. In wood-craft this design is usually found at the top of pillars or pekkda.

- Betel leaf: This motif is used in various adaptations.

4. MISCELLANEOUS

-

Tiringa tale: The design considered to be the ultimate test for the craftsman, this motif is composed of liya patabased on the vaka deka with paturu (wedge), and suli (scroll-worl design) adornments. This design integrates all the components in a harmonious whole. This design is widely found in present-day wood-carvings in combination with the makara torana.

- Arimbuwa: This is a geometrical design with a row of small dots and circles set between two parallel lines; it is found as a border of a liya vela or as a border framing a larger design. Several examples of this design are found in the wood-carvings of Embekke.

- Gal binduwa: Another geometric design, this consists of rectangles and circles placed alternately between a set of parallel lines forming a border design. In wood-work this motif is carved as a decorative feature on beams in temples and other places of worship or around the carved panels on pillars.

- Kundirakkan: This is a diamond-shaped border design, with forms such as del-ahe (net design). Sometimes this motif is found in combination with the arimbuwa motif or a series of circles or discs between two boundary lines. This combination is found extensively on carved wood panels. This motif has a symmetrical appearance in its various combinations.

- Tharaka piyum: This is a motif resembling a star.

- Chevron: This is an isosceles triangle motif, which, in its elongated form is found as a border design.

- Dagabo: This is a Buddhist symbol.

- Christian cross & the cherub: A recent development is the depiction of wooden carvings of the cross and the cherub motifs in churches.

CRAFT LOCATIONS

- Anuradhapura district (270 kilometres from Colombo): Wood-carving is found in the villages of Habarana, Wahamalgollewa, and Kepitigollawa. Wall plaques are made in the village of Kokawewa and wooden trays in the villages of Mihintale and Karuwalagaswewa.

- Kandy district (225 kilometres form Colombo): Wood-carving is found in the villages of Embekke, Gunnepana, and Kalapura.

- Kurunegala district (close to Colombo): Wood-carving is found in the villages of Mangalagama, Maspotha, Padeniya, and Minuwangete.

- Matale district (close to Kandy): Wood-carving is found in the villages of Dehideniya, Elkaduwa, and Marukona.

- Moneragala district: Wood-carving is practised in the villages of Etimale, Uvapelawatta, and Kotamudara.

- Ratnapura district: Wood-carving is found in the villages of Minipura and Pelmadulla; wall plaques are made in the village of Marapona.

CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES

The demand today is innovative variations of traditional designs and for products that combine aesthetic appeal with utilitarianism. Popular contemporary products include table-lamps, caskets, trays, carved fruit bowls, and ornamental wall hangings, all innovatively designed. Some items that are popular as souvenirs are wall plaques, leaf trays from calamander and nadun woods, paper knives, and calendar stands made of satin wood. Among the problems encountered by craftspeople today are dwindling supplies of timber like ebony and quality soft and hard woods. The government will probably have to intervene to rectify this shortfall by creating special plantations for sourcing raw material for the wood craft, especially so that the forest resources of the country are not depleted.

Gallery

YOUR VIEWS

PRACTITIONERS: INDIA

Access 70,000+ practitioners in 2500+ crafts across India.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

10,000+ listings on arts, crafts, design, heritage, culture etc.

GLOSSARY

Rich and often unfamiliar vocabulary of crafts and textiles.

SHOP at India InCH

Needs to be written.