Surface embellishments on textiles is a centuries old tradition and the cloth fragment excavated at Mohenjo Daro was dyed purple with madder root and the continuity of this tradition is born out by the flourishing trade of dying and decorating textiles all over Pakistan.

The noteworthy traditions include block printing, especilly Ajrak, the tradition of Roghan painting, tie and dye and other methods.

BLOCK PRINTING

Block-printing is practised all over Pakistan and its best known centres are in Punjab, Sindh and NWFP.

Cotton fabric is block-printed with simple patterns for furnishings and for women’s garments at Swabi in Mardan district and Haripur in Hazara. In the Punjab block-printers have considerably diversified their craft. The reproduction of patterns and motifs – floral, geometric and sculptural – evolved in the Mughal period continues but at the same time intense competition has forced a search for new patterns. Remarkable success has been achieved in the printing of khaddars for curtains and upholstery and the magnificent designs traditionally printed on dastarkhwans (dining cloth) have been improved further. There are sizable communities of block-printers in small towns all over the Punjab and the Frontiers and each center has developed designs to suit the local environment and the taste of the people around and the tradition continues with varying degrees of refinement.

The main centres of cotton-printing were Lahore, Multan and Kot Kamalia (simply called Kamalia today) which lies between them. Other smaller centres include the small town of Kahror Pakka, between Multan and Bahawalpur. The prints made in Lahore in the nineteenth and early twentieth century are characterized by a softer palette and somewhat finer ground cloth. The muted colours ad less bold designs, drawing largely on Persian kalamkari designs rather than Punjabi architectural motifs, found favour especially with Europeans at that time, and many Lahore printed bedspreads can still be found in British homes. After a long break, block printing on silk and synthetic cloth has been revived in Multan and Karachi.

The Lahore tradition may be said to have been inherited today by the block-printers of Kahror Pakka whose products also tend to be in a somewhat Persian style. The quality of the block-carving is high and the fabrics are printed from finely carved blocks of shisham-wood in complex designs, with up to four different colours plus the black outline, each requiring a separate block., and, with a little more attention paid to the printing itself, block-printing could be re-established as a major craft of the Punjab.

In Sindh there are ancient and diverse traditions of dyeing and printing cloth all over, from the single coloured red laso or hik rango to the complex resist and mordant-dyed ajrak. Block printing (chur) uses specially carved blocks of wood (por) sequentially dipped in dyes and stamped on cloth. Sheets, coverlets, wall-hangings, qanats (cloths used for screening off areas), dastarkhans (tablecloths), shoulder cloth, wraps of all sizes and women’s costume are all chur printed in a variety of patterns and colours.

AJRAK PRINTING

At present with the unbroken link in the ajrak tradition Sindh can boast a block-printing tradition that has survived all vicissitudes. The Sindhi employ the most ancient technique to block-print their ajraks. Instead of printing the colours directly, as in later techniques of block-printing, a mordant and a resist is stamped on to the cloth which is then dipped into a series of dye baths. The pattern printed with a resist remains white. When a mordant is used the dye only adheres to the print. Since ajrak means blue in Arabic, it is believed that indigo traditionally dominated the colour scheme as it does in contemporary production. Traditional colour combinations are blue and red, red, white, blue and /or black, as well as black and white. Yellow and green, once derived from pomegranate rinds, are sometime added especially by block-printers of Tando Mohammad Khan, one of the leading ajrak producing towns. The unique geometric patterns are typically composed in a series of borders to enclose a contrasting centre design.

The ajrak remains a popular Sindhi fashion and is traditionally used for skirt material, men’s turbans and women and men’s chadars and dupattas, as a shawl, and sometimes it is converted into a hammock for a child, slung from the trees. It is very commonly spread on the beds as bed sheet and coverlet. Ajraks are available in yardage as well as stitched into tablecloths and matching napkins, curtains and bedspeads with matching cushion and pillow covers.

The Ajrak, is a name derived from ‘Azrak’, which means blue in Arabic and Persian.

In Ajrak to acheive perfect synchronization the block-maker brings a sense of unity, coherence and order in the patterning of the printing block.

The repeat pattern, which gives the design its character, is determined by a grid system. It is the equilibrium between the centripetal and centrifugal tendencies which form a unit, and that is translated into a pattern.

In the construction of geometric patterns, the compass and ruler are the two major instruments used by the block-makers.

The wood most suitable for carving is from the indigenous trees of Sindh. The Babur, Keekar, Tali (Sheesham)

From the seasoned wood, a block is cut to the required size and sanded on a stone to get a levelled plane surface, which is then checked out by the edge of a steel rule.

Diagonals are marked, and the square is quartered, and then further sixteenth. The pattern drawn on paper is transferred by etching fine lines onto the surface of the block.

It normally takes the block-maker a week to carve a complete set. A set usually comprises of 7 blocks. Asl (1 block) for kiryana printing; kut (1 block) for datta printing; phulli (1 block) for gad printing. Two blocks each of kharrh and meena are carved so that two artisans can print simultaneously.

The complicated process of Ajrak making differs from centre to centre, and craftsman to craftsman. The ustos vary the proportions of the ingredients used and the duration of time required for a certain stage of the process, according to weather changes, fabric structure and availability of raw materials.

Teli Ajrak is famous for its unique and magical properties. When worn, used and washed frequently, the colours instead of fading, become more brilliant and luminous; in fact the fabric eventually gives way, but the colours remain fresh. This traditional method of making an Ajrak involves more time and effort. Today, very few craftsman go through this tedious process completely, and instead, take short cuts due to which variations are emerging.

SILK SCREEN PRINTING

In the recent past silk-screen printing has developed as cottage and small industry in Karachi, Hyderabad, Multan and Lahore. The printers employ the international technique of photo silk screening. Their prints are often inspired by traditional block-print and ajrak design. Some of the prints contain as many as five colours that are registered with separate screens.

ROGHAN/ WAX PAINTED CLOTH

One of the more distinctive and unique traditions associated with the embellishing of textiles is the roghan or wax-cloth work technique practised at Peshwar In this technique cotton or silk cloth is decorated by applying a soft, wax-like substance (roghan) produced from the oil of the safflower seed. Pigments such as orpiment and red lead are added to the roghan, and the ductile substance is manipulated on to the surface of the cloth with a metal stylus. The craftsman begins his work by putting a small portion of the paste on his hand. He pulls out fine filaments of the material with a stylus, attaches it to one point on the cloth and then stretches it to sketch the straight line and curves that make up the painting. The process has been likened to “drawing a pattern in thick treacle by means of a skewer”, but in spite of this unwieldy technique, surprisingly fine lines and designs are produced by manipulating the soft gum on the surface of the fabric with a moistened fingertip. A silvery effect is sometimes obtained by dusting the roghan with powdered mica. The roghan technique is traditionally associated with the Afridi tribe of Pathans, who live in the area around Peshwar and Kohat, and this type of cloth was formerly made commercially in Peshwar. The Afridi tribe is known for printing multiple colours of wax with metal blocks. Painting with wax is now practised by craftsmen in Peshwar, Lahore, Karachi, and Quetta. The motifs are generally delicate animal figures and landscape. It could be used for garments as well as for furnishings, but is perhaps better suited to large-scale patterns, and became popular with European customers for hangings.

TIE-DYEING

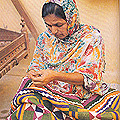

A notable technique developed over the centuries is that of resist dyeing and one of its manifestations is the tie and dye technique. Oral traditions relate that tie-dyeing techniques (bandhani) travelled from the eastern areas of Sindh to Kutch and Gujarat. Bandhani is a style of patterning cloth by tying or knotting specific areas to protect then from the dye (bandhana is ‘to tie’). The cloth is prepared with soap and treated with oil and an alum mixture before it is tied. Bandhani patterns vary in intricacy from a single dot to a combination of borders and medallions. The prepared cloth is first marked out with a dotted pattern; it is folded into four, steamed and then pressed over a board embedded with nails to obtain an imprint, or printed with a charcoal and water mix. It is then sent to a bandhnari or knotter, usually a woman, who picks up a tiny piece of cloth from each marked dot and ties it in a knot (bindi) with a piece of waxed string. When trying has been completed the cloth is taken over by a dyer (Khatri) who dips it into the dye required for the ground colour. After drying, the knots are unfastened, the parts tied having resisted the dye to form white circles. This is the simplest chundari (or chunari) pattern. In more complex designs such as the flower garden (phulvadi), knotting further areas and dyeing are repeated for each colour.

BATIK

Among the resist dying methods practised in Pakistan is the embellishing of fabrics with the batik technique. In this method the area not to be dyed in a particular stage or to be dyed lightly is covered with wax. When the piece is dipped in dye solution the area not covered with wax is dyed, and the rest is left unaffected. Also the hot bath melts some of the wax that flows on to the areas meant to be dyed and this portion receives a lighter colour. The more intricate designs are mapped out on a shawls and scarves.

RILLI

An important Pakistani craft which combines several decorative techniques i.e. printing, applique and, of course, embroidery, is called ‘rilli’ which means patchwork. In early days inexpensive and small pieces were stitched together to form a ‘chaddar’ or bed sheet. But nowadays it is available in different varieites, colours and designs. It can be a most valuable and expensive gift.

Gallery

YOUR VIEWS

PRACTITIONERS: INDIA

Access 70,000+ practitioners in 2500+ crafts across India.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

10,000+ listings on arts, crafts, design, heritage, culture etc.

GLOSSARY

Rich and often unfamiliar vocabulary of crafts and textiles.

SHOP at India InCH

Needs to be written.